As a nation based on convict immigration we sure enjoy creating laws. The essence of journalism is uncovering truth that in the eye of the public is valuable. What happens when truth conflicts with the government? This explainer will dip a toe into Media Law, to discover which laws affect journalists in their research, source protection and publishing, specifically looking at national security and freedom of information in regards to the AFP raids on the ABC. This overdramatic event shines a light on some fairly draconian laws here in Australia and begs the question, Is investigative journalism being categorised as a crime?

As journalist Ross Coulthart put it, ‘I suspect the metadata laws are part of an opportunistic push by our police and intelligence services to use the current national security crisis to try to shut the door on journalistic investigation into their activities’

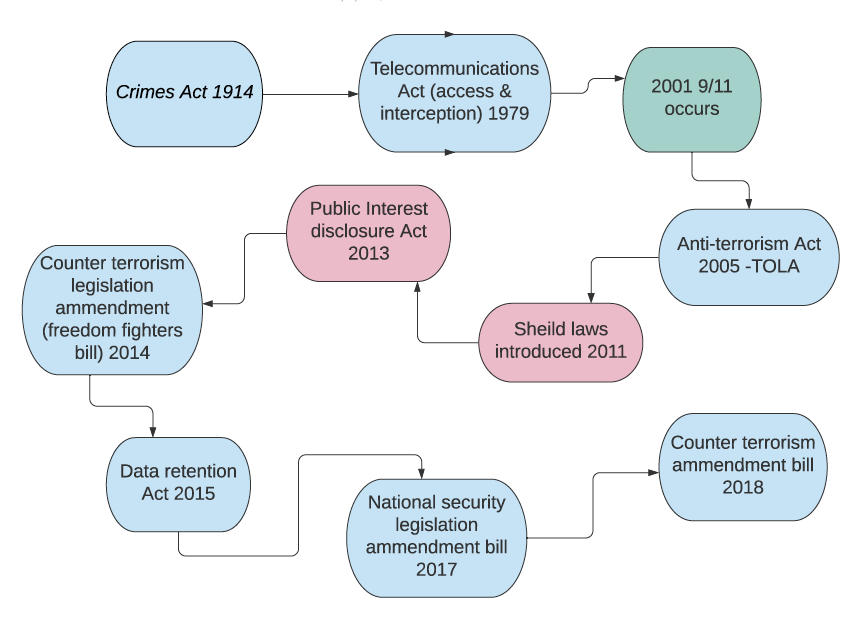

The ramifications from 9/11 were felt globally and enabled our government to create more legislation around National security and anti-terrorism. This has the guise of implied safety for our nation, but inherently allocates more powers to those that be. Australian parliament has led to the passage of 82 new or amended laws in response to the threat of terrorism, silencing journalists and muddying the waters for media. Safety, freedom, secrecy and scrutiny of the government all are intertwined in an unclear manner but must be dissected by upcoming journalists as we demand the continued right to expose public interest stories.

On June the 5th, 2019, the Australian Federal Police raided the ABC to seize any files that related to the leaked, classified ‘Afgan files‘ which reported on the brutal, unwarranted culling of unarmed civilians by Australian soldiers in the war in Afghanistan. The material from this ongoing correspondence had already been published by the ABC, namely by Dan Oakes and Sam Clarke in 2017, who had received the information from whistleblower, David McBride a military lawyer for the special forces. Special forces are protected under national security laws thus making information leaks of their wrongdoings illegal.

The chart above gives a brief timeline of Australia’s law affecting journalists. It’s a dizzying process to interpret our law’s but as the blue denotes a negative bias and the pink a positive, it appears that the laws are mounting against journalists and by in large the freedom of media. The 1914 Crimes Act in Australia, which imposes harsh penalties on Commonwealth government employees who disclose information that they have obtained in the course of their official duties to anyone outside of those duties, is the building block for our federal laws. Our post 9/11 landscape has created a dissonance between us and the government, citizens don’t know what is being protected and journalists run the risk of inadvertently, or advertently in the case of the Afgan files, exposing wrongdoing that is protected by law. This leaves little space to serve our duty to the fourth estate especially considering there is no defence of public interest when a journalist reports a miscarriage of justice.

It is important to note that Australia has more legislation around national security than anywhere else in the world essentially rendering Oakes and Clarke defenseless in any traditional sense. National security and ‘the war on terror’ is the trump card. These strange, Authoritarian laws also cause havoc for journalists trying to cover the asylum seeker issues and the secrecy around detention centres. The desire for the government to suppress information around special interest operations appears to be fear based and throws a spanner in our democracy.

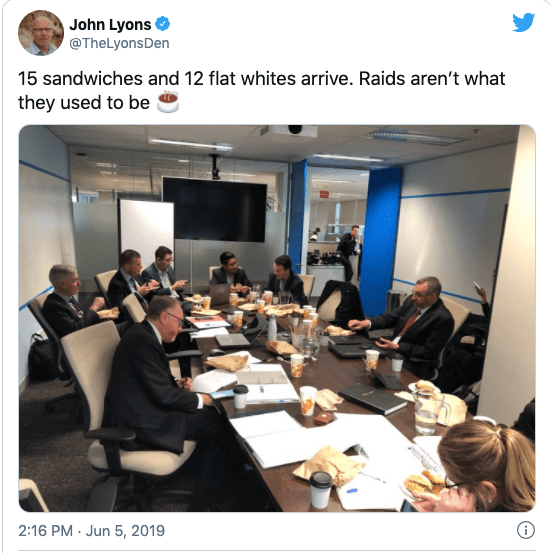

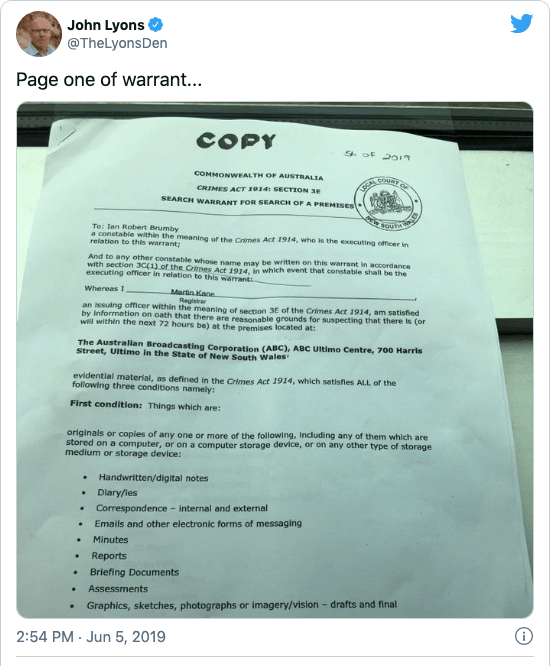

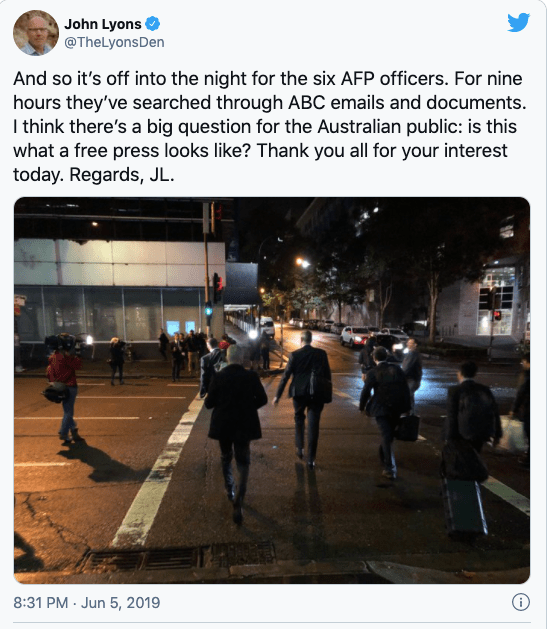

Journalist defence lies in Shield law, which is a term describing an array of laws that offer varying levels of protection to journalist who would otherwise face a disobedience contempt charge for refusing to reveal a confidential source (Pearson & Polden, 2019). And more importantly in this case, a Public interest defence which can be described as a benefit to society, the public or the community as a whole. It is interesting to note that a public interest advocate is assigned to you, should you be served with a warrant. In regards to the ABC raids, a warrant was issued without their knowledge and the ensuing collection of data from their office went on for nine hours. John Lyons was able to tweet live as it unfolded, cautiously staying in step with the law.

This instance depicts the reach of law and how brazen it can be, the warrant is delightfully vague and all encompassing, allowing the AFP to collect and detain any file they wished in an unchallengeable attainment of metadata. Even erased Metadata poses a threat to us, as governments can retrieve deleted files, intercept correspondence and make changes at will, ‘off the record’ seems like a ghost of the past.

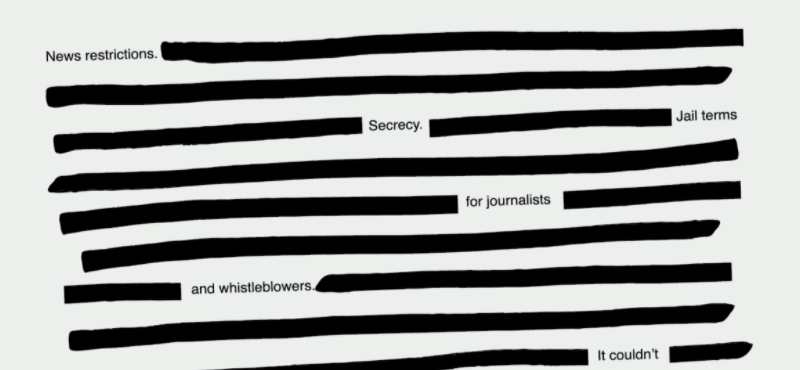

An unexpected act, the raid garnered heavy national and international attention and was seen as an obvious attempt at intimidation, and a heavy handed warning for other journalists and media companies. The sentiment that our freedom of press is under assault is apparent. It’s also important to note that the penalties for breach of many of these laws is several years in jail, for example the National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Bill 2017, applied jail terms of up to 20 years for journalists reporting in the public interest. An exorbitantly high price to pay for your job.

The ABC challenged the AFP raids in court and subsequently failed, despite them not finding any material that was a direct threat to national security, this feels like an echo of the actual war on terror and its overt inability to deliver any weapons of mass destruction. Clarke and Oak’s were left dangling precariously with the threat of prosecution by the CDPP but have now been cleared, with the finding of, no public interest to prosecute. A considerable relief for them both but this incidence has left a sour taste in the mouths of Australians, with secrecy laws rendering problematic for our freedoms.

Renegotiations do appear to be at foot to some degree, after two seperate parliament inquiries into the raids and politicians decrying there belief in press freedom. This episode has also united media bodies. For journalists the MEAA (Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance) is our voice and they are pushing for a media freedom act, lest Orwell’s prophecies come to life, but perhaps we are already governed by the ministry for truth.

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jsAn ally of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny decided to play the piano while police raided her home, the latest in a string of raids targeting associates of the Kremlin critic. https://t.co/CZTISTiCsK pic.twitter.com/e912VyLxVg

— ABC News (@ABC) January 28, 2021

Reference : M Pearson & M Polden, 2019, The journalist’s guide to media law, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest.

Leave a comment